Russian Avant-Garde Designers

This exhibit shows the most well-known period of Russian art history from design achievements perspective, ranging from Varvara Stepanova’s patterned fabrics to Aleksandr Rodchenko’s workers’ club projects. The exhibit will also tell about the design of cult objects, such as Moscow’s Melnikov House, the Shukhov Tower as well as the Mukhin drinking glass, which Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina designed.

Design in Russia developed differently than in the West; Russian Avant-Garde artists’ ideas on restructuring the world and society, as well as the creation of a universal individual who possessed secrets on creating the universe, resisted the desire to quickly sell goods. Those artists created the new reality, which in fact was the fourth dimension, with help from a “higher intuition” and the means of a universal singularity; color in Suprematism and shape in Constructivism, deprived not only of spatial orientation, but also of time orientation. Only through the energy of color and form, and with help from the universal singularity was it possible to relay any sort of sensory input to the viewer.

Painter and art theoretician Kazimir Malevich and his students from “The Champions of New Art Movement” (UNOVIS) already began restructuring society after Russia’s October Revolution of 1917. They designed new forms of clothes, fabrics and dishware with the goal to change an individual’s surroundings, consequently changing that person. It was this and the manifestation of new art was that made Russia’s design phenomenon a part of creating this new world. Malevich’s experiments with color and its influence on the individual formed the basis for the theory of chromatics -- one of design’s fundamental aspects. The year 1920 also saw in Moscow the merger of Free State Art Studios Nos. 1 and 2, respectively created from the Stroganov Art School and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture after the October Revolution, resulting in the Higher Art and Technical Studios (VKhUTEMAS).

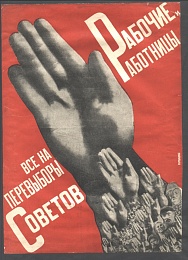

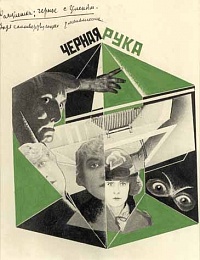

Avant Garde artists, such as El Lissitzki, Vladimir Tatlin, Stepanova, Rodchenko, along with abstract painter Vasiliy Kandinskij, taught at VKhUTEMAS at various times. Rodchenko and Lissitzki stood out the most in the graphic design of that era. Their font compositions, collages, photomontages and poster graphics are an important part of world design’s heritage. The artists created other projects, making discoveries in various interconnecting fields, and later implemented new principles for organizing exhibition stands, architectural ensembles, skyscrapers and specific types of furniture.

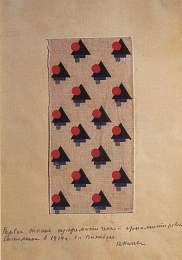

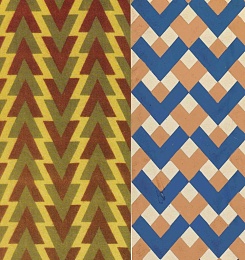

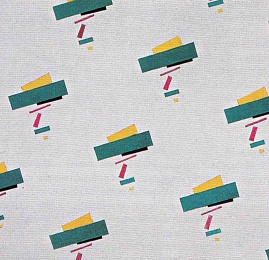

The complex approach to creating items was the most important part of Tatlin’s art program, which taught the culture of materials and also taught students to take functional and organic factors into consideration. Stepanova was a professor for at VKhUTEMAS’ textile division and designed in 1924 with compatriot artist Lyubov Popova models for sport and everyday clothing. Stepanova also developed patterned fabrics for Moscow’s Printworks Factory No.1, and about 20 out of the 150 decors that Stepanova created made it onto calico.

The theatre, which reoriented the leaders of figurative art towards the social aspects of creativity, ushered an important role into early 20th-century design. Theater director, actor and producer Vsevolod Meyerhold provided the stage for practical realization of ideas to Tatlin, Popova, Rodchenko, Stepanova and the brothers Vladimir Stenberg and Georgy Stenberg.

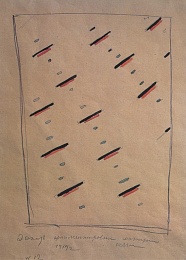

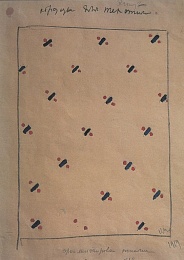

TEXTILE

Avant-garde artists’ textile sketches embodied the main tendencies of art at that time. Balancing between craftsmanship and high-end art, between popular taste and avant-garde theoretical calculations, the artists who created small and understated patterns paradoxically put into them the deep and formative processes of early 20th century art and outlined its future development.

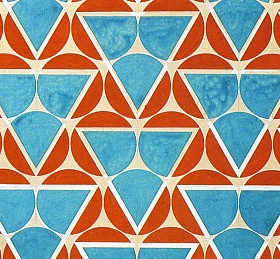

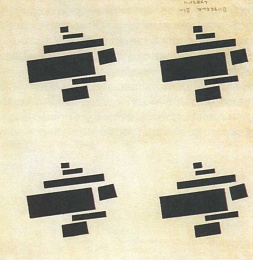

“Clean” surfaces and the new metaphysics of color free from reality helped to create ornamental forms, which artists called Suprematism. Malevich was the ideologist, leader and founder of this trend. Malevich’s contemporaries saw Suprematism’s decorative potential as a style. They believed that Suprematism was decorative in the purest sense and should find use a new style that is at once marvelous as well as strong.

The Kiev-based Verbovka Village Folk Centre Textiles, which artist Natalia Davydova founded in 1915, first used Suprematism on textiles, such as patterns on dresses, carry bags and shawls. Popova, Nadezhda Udaltsova and Olga Rozanova also created suprematist patterns and fashions for embroidery and appliques.

Suprematism became a concept for the singularity of global creativity, a concept of the “New World Order.” It appeared in the physical-spatial medium on the surfaces of items – walls, dishware, fabrics and clothes. Examples of fabrics with Suprematist patterns, using sketches from Malevich, Ilya Chashnik and Nikolai Suetin, appeared in 1920 at the Vitebsk Art School. Malevich also developed sketches of suprematist dresses that were to stylistically match an indiviual’s surroundings and be a part of the new world.

Artist-designer Aleksandra Ekster, along with Rodchenko, Stepanova and Popova, later found expression in the task to create new fabric designs during a new level of Suprematism’s development. Constructivists offered objectless patterns for printed fabrics. Introduction of new patterns into regular use became a method for organizing the socialist way of life. Popova and Stepanova developed fabric samples in 1924 for the First State Textile Print Factory. Those samples went into production for mass consumption, and by summer of that same year all of Moscow was wearing the constructivist fabrics. Those patterns in essence became the Soviet Union’s first fashion.

Popova and Stepanova also designed patterns with Soviet symbolism, though the most interesting ones were those with simple geometric shapes. The Constructivists learned from Suprematism’s “objectless” painting a very careful analysis of proportional and spatial ratios, rhythmic arrays, dynamic, optical and spatial effects, shifts, shape displacement and the combination of planar and volumetric elements, thus allowing them to propose innovative solutions.

An evenly organized structure distinguished the Constructivists’ fabric projects from those of the Suprematists; The former used a programmed morphogenesis method, with the most simple geometric shapes as a motif.

Ivanovo Agitprop Textiles

Creation of agitprop fabrics at Ivanovo, one of Russia’s largest industrial centers, was a short but extraordinarily important step in its history. Textile production at that time was an arena to realize strategies for a new, proletarian art, and the Ivanovo agitprop fabrics came into bloom.The Ivanovo masters created the first fabric patterns for that trend in the mid-20s, and recent graduates from VKhUTEMAS – the first generation of Soviet artists – took part. They also faced the ambitious task of embodying revolutionary ideology into the fabrics’ design, which was to be accessible to the masses and to reflect the pathos of industrialization, electrification and collectivization.

Agitprop comes from the words “agitation” and “propaganda.” Its purpose was to present political messages via various media, such as films, plays and books.

WORKING CLOTHES

“Widely available clothing should consist of simple geometric forms, such as rectangles and squares; the rhythm in them must fully reflect the consistency of form” – Russian-French painter and designer Aleksandra Ekster.The simplicity of clothing design in the 1920s was not only an absolutist phenomenon for geometrical forms, but also indicated industrial-level production. This is how development of functional working clothes became a trend in Soviet design of the 1920s.

The constructivists designed a “new form” for working people, in order to replace “any old clothing.” They ascertained that clothing in the new socialist era should in its own way become a professional tool, and thus put forward the idea of “prozodezhda,” or working clothes.

Stepanova outlined new principles for a functional approach to clothing design in a speech that she made at the now-defunct Institute of Artistic Culture.

“The main design principal in a present-day suit is comfort and practicality. There is no suit as such, but rather a suit for any sort of production activities. The way to design – such as the job assignment and material design, the activities that the wearer plans to carry out – is the actual method of cutting them,” she stated.

Constructivists considered fashion to be a bourgeois phenomenon and negated the continuity of clothing shapes with revolutionary zeal.

The concept of working clothing came to fruition on stage, and Popova designed them for Meyergold State Theatre’s production “Le Cocu magnifique” (April 1921). Stepanova also designed for the same theatre clothing for “Tarelkin’s Death,” (November 1922), while Rodchenko’s designed casualwear respectively for Vladimir Mayakovsky’s and Anatoly Glebov’s plays “The Bug” and “Inga” (1929).

ARCHITECTURAL FORMS / INTERIOR

The rise in creative artistic culture from 1910 through to 1920 appeared to have simply bypassed design per se. We know little about product design of this time, likely due to economic and organizational reasons.Lissitzki was drawn to futuristic architecture, having almost completely bypassed concept design.

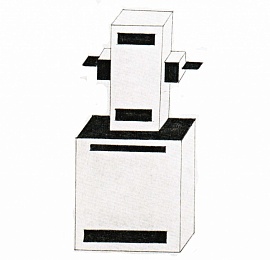

Vladimir Tatlin, Malevich’s eternal rival, turned out to be the most the consistent of all concept designers from that generation of pioneers. He and his students at VKhUTEMAS focused on furniture, such as console chairs, collapsible chairs and convertible sofas, clothes not only for the stage but also for practical use, dishware and even ovens. The “Letaltin” flying machine, which glorified Tatlin, was an artistic exhibition.

The absence of modern production created the search for a furniture design spec in the Soviet Union of the 1920s, though only bits and pieces from then have made it into the contemporary era.

Tatlin came upon the idea to use steel pipes while he taught at VKhUTEMAS, the same time that Bauhaus came into fashion. He thus created in 1927 with one of his students a console chair from rusted steel pipes at the same time as the famous console chair of Hungary-born modernist, architect and furniture designer Marcel Breuer.

A Working Club’s design-project, which Rodchenko presented in Paris, was an example of a completely different line in furniture design. Rodchenko used wood as part of a design chairs, tables, armchairs and shelving-partitions. Many of the items on display suggested transformation and change of function, despite the solid wood masses’ static stability.

The furniture that architect and urban planner Nikolai Milyutin built for the Soviet Finance Ministry’s own penthouse was not meant for replication; The unavailability of any other type of furniture prompted the ministry to design and build its own.

The built-in kitchen module that architects Mikhail Barshch and Solomon Lisogar designed for flats, which outlived the very flats, for which they were intended. Those modules would at first comprise a part of a “converted home”, from a regular apartment to a communal one. A group of architect Moisei Ginsburg’s students built six such buildings, called Gosstrakh.

The kitchen module was in other homes of the 1930s that contained traditional apartment planning, however, in anticipation of module furniture for compact kitchens in the Khrushchyovka apartment buildings, which appeared in the 1960s.

The Ginsburg group also developed the residential units themselves, which carried Latin-lettered designations, in the hopes of a complex architectural-designer solution. The residential apartments in Moscow’s Narkomfin Building contained not only the kitchen modules, but also interior paint for the interior was in cold and warm colors, with Bauhaus professor Hinnerk Scheper in cold and warm colors.

STATE PORCELAIN WORKS / LABORATORY OF SHAPES

Malevich and two of his students –graphic artist Nikolai Suetin as well as artist and designer Ilya Chashnik -- moved at the end of 1922 from Vitebsk, where conceptual art was first born and underwent its first, crucial stage of development, to what was then Petrograd, but now known as St. Petersburg. It was there that they almost immediately joined the State Porcelain Works (GFZ) as artists.The Suprematists’ arrival was an event for the plant. Having rejected old culture, the art reformists created a new range of items. Malevich suggested in 1923 to plant director Nikolai Punin the creation of a special division, a “laboratory of shapes,” which would focus on the search for new shapes. The items that Malevich and his students created in this laboratory predicted in many ways the path for future architecture.

Malevich placed conceptual shapes on regular, primary elements for dishware. This resulted, for example, in a spherical teacup becoming a half-sphere. The handle became an impenetrable square, thus becoming an uncomfortable-to-use, though extremely original teacup.

Malevich also did similar things with kettles, which were impossible to use, yet inspiring upon examination.

Suetin and Chashnik themselves became familiar with the area of large volumetric shapes and even painted Malevich’s creations; They painted the very same half tea cups many times and made great strides in the field of shape creation.

The Suprematists’ active work did not last for more than a year, however, as they became victims of the factory’s economic reforms of 1924.

“Not one product from the factory was so highly appreciated either within the country or in the West, and not one of them had received such a volume of orders for consumer use, having not only a utilitarian but also aesthetic purpose, as the Suprematist dishware, although the Suprematists themselves long ago became redundant and the plant now only repeats their old examples,” the factory’s artist and de facto chronicler Yelena Danko sadly stated in 1929.

КАЗИМИР МАЛЕВИЧ

1879 - 1935

Живописец, теоретик искусства. Один из лидеров русского авангардизма 10-30-х гг. Основоположник одного из видов абстрактного искусства - супрематизма, основанного на сочетании простейших разноцветных геометрических фигур, образующих асимметричные, пронизанные внутренним движением композиции ("Чёрный квадрат", 1913). В 1913 оформил в Петрограде постановку оперы М. В. Матюшина " Победа над солнцем", в 1918 - первую постановку "Мистерии-буфф" В. В. Маяковского. В 20-х гг. с помощью абстрактных пространственных композиций - "архитектонов" - изучал язык пластических искусств, создавал проекты бытовых вещей, рисунки для текстиля и др. В начале 30-х гг. вернулся к изобразительности (" Девушка с красным древком ", 1932)

ЭЛЬ ЛИСИЦКИЙ

1890 - 1941

Российский архитектор, художник-конструктор, график. Один вы выдающихся представителей русского авангарда. Совместно с Казимиром Малевичем разрабатывал основы супрематизма. Один из создателей нового вида искусства — дизайна. В 1921—25 жил в Германии и Швейцарии. Член Аснова и нидерландской группы «Стиль». Разрабатывал проекты высотных домов, трансформируемой мебели, методы художественного конструирования книги («Хорошо!» В. В. Маяковского, 1927)

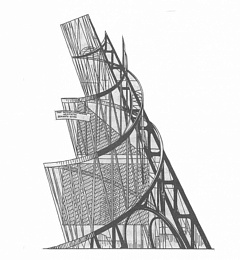

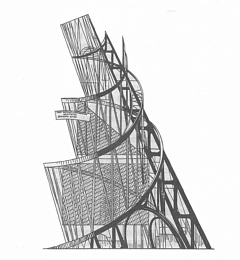

ВЛАДИМИР ТАТЛИН

1885 - 1953

Один из крупнейших представителей русского авангарда, родоначальник художественного конструктивизма. Проект Памятника III Интернационала (1919—1920) Татлина с вынесенной наружу несущей конструкцией стал одним из важнейших символов мирового модернизма и своеобразной визитной карточкой конструктивизма.

Татлин является одоначальником советской школы образного дизайна. Он подчеркивал, что любая вещь должна быть удобной, прочной, целесообразной и нравиться ее обладателю. Художник обязан создавать вещи, формирующие новый быт, как цельную среду обитания. И здесь, по его мнению, необходима совместная работа с инженерами и техниками, а также комплексный подход. Татлину принадлежат проекты печей, новые конструкции кроватей, модели одежды и посуды.

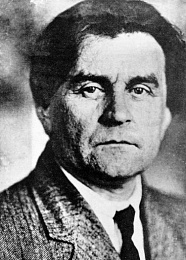

ВАРВАРА СТЕПАНОВА

1894 - 1958

Советский художник-авангардист, представительница конструктивизма, дизайнер и поэт, жена и соратница Александра Родченко.

Степанова выступила также и как радикальный новатор текстильного дизайна, исполнив 150 рисунков (для Первой ситценабивной фабрики, 1924–1925) В лучших своих теоретических выступлениях 1920-х годов отстаивала независимость нового искусства, понимая его как «чудо», которое не может быть постигнуто в узкоутилитарном, чисто функциональном смысле.

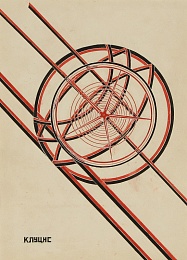

ГУСТАВ КЛУЦИС

1895 - 1938

Художник-авангардист, представитель конструктивизма, один из создателей искусства цветного фотомонтажа. В 1922–1924 создавал проекты одежды конструктивистского стиля. В 1927 выполнил витражи для павильона Всесоюзной полиграфической выставки («Ленину —вождю и организатору Октября», «Мы десять лет учимся, строим, побеждаем»). Принимал участие в оформлении советского отдела на Международной выставке прессы в Кельне (1928), а также создавал экспозиционное оборудование для Выставки советского искусства в Брюсселе. В зрелый период творчества был убежденным приверженцем «производственного искусства», отрицающего станковизм и изобразительность (за исключением фото- и кинообразов).

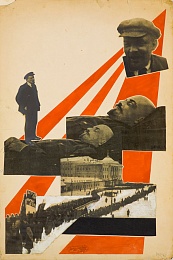

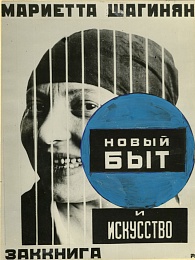

АЛЕКСАНДР РОДЧЕНКО

1891 - 1956

Советский живописец, график, скульптор, фотограф, художник театра и кино. Один из основоположников конструктивизма, родоначальник дизайна и рекламы в СССР. Работал совместно со своей женой, художником-дизайнером Варварой Степановой.

В 1925 году был командирован в Париж для оформления советского раздела Международной выставки современных декоративных и промышленных искусств (архитектор советского павильона — К. С. Мельников), осуществлял в натуре свой проект интерьера «Рабочего клуба». Рекламные плакаты А. Родченко удостоены серебряной медали на парижской выставке 1925 года Применил фотомонтаж для иллюстрирования книг, например, «Про это» В. Маяковского (1923). С 1924 занимался фотографией. Как фотограф, Родченко стал известен благодаря экспериментам с ракурсом и точками фотосъёмки. Одновременно работал в кино (художник фильмов «Москва в Октябре», 1927, «Журналистка», 1927—1928, и др., разрабатывая оригинальную мебель, костюмы и декорации. С 1933 работал как художник-оформитель журнала «СССР на стройке».

ЛЮБОВЬ ПОПОВА

1889 - 1924

Русский и советский живописец, художник-авангардист (супрематизм, кубизм, кубофутуризм, конструктивизм), график, дизайнер. Попова разрабатывала оформление к спектаклям для театра Мейерхольда, Камерного театра. Занятия конструктивизмом привели художницу к отрицанию станкового искусства и обращению к деятельности на производстве. Эти тенденции нашли отражение также в творчестве А.М. Родченко, А.А. Экстер, А.А. Веснина. Свои работы они представили на выставке «5x5=25». Попова вместе с В.Ф. Степановой работала в области промышленного дизайна на Первой ситценабивной фабрике в Москве.

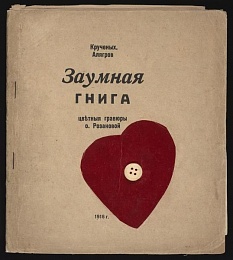

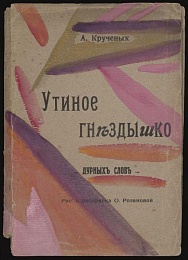

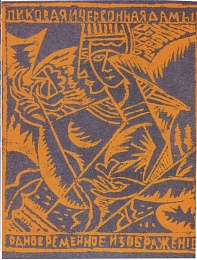

ОЛЬГА РОЗАНОВА

1886 - 1918

Одна из крупнейших художников русского авангарда с уникальным колористическим талантом. Пройдя несколько направлений авангарда, вышла через супрематизм к цветописи, на несколько десятилетий предвосхитив развитие абстрактного искусства.

Интересовалась вопросами народного искусства. Высшего напряжения дух творческого эксперимента достигает в книжных работах Розановой. Она как бы принимает эстафету из рук Гончаровой, исполнившей в 1913 году свою последнюю литографированную книжку. С этого времени Розанова становится активнейшей участницей многих футуристических изданий. Художница, не менее одаренная, чем Гончарова, талантливый живописец и график, оставивший глубокий след в истории русского предреволюционного эстампа.

АЛЕКСАНДРА ЭКСТЕР

1882 - 1949

Русско-французская художница-авангардистка (кубофутуризм, супрематизм), график, художница театра и кино, дизайнер. Представительница русского авангарда.

Была одним из основоположников стиля «арт-деко».

Как художник театра и кино работала над спектаклями Московского камерного театраА. Я. Таирова, фильмами («Аэлита»Я. А. Протазанова) и др.

В качестве дизайнера по костюмам сотрудничала с Московским ателье мод, работала над созданием парадной формы Красной Армии (1922—1923) В 1924—1925 годах занималась оформлением советского павильона на XIV Международной выставке в Венеции и подготовкой экспозиции советского отдела Всемирной выставки современного индустриального и декоративного искусства («Арт Деко») в Париже.

НИКОЛАЙ СУЕТИН

1897 - 1954

Российский советский художник, мастер дизайна, графики и живописи, представитель авангарда в его супрематическом варианте, реформатор русского фарфора. Сыграл исключительно важную роль в процессе предметного выражения идей основоположника супрематизма, – тех идей, которым сам Малевич лишь весьма редко придавал декоративно-прикладное воплощение. Как художник по фарфору он произвел настоящую революцию, радикально видоизменив как декор, так и саму структуру изделий – в результате отказа от каких бы то ни было исторических стилизаций ради элегантно-строгого геометризма. Позднее вслед за своим учителем перешел от чистой геометрии к «метафизическим», условно-знаковым фигуративным образам, что сказалось и в станковом (крестьянские мотивы конца 1920-х годов), и в декоративно-прикладном (сервиз Бабы, 1930) творчестве Суетина. В 1935 создал памятник в виде куба на могиле Малевича в подмосковной Немчиновке (не сохранился).

|

|