SOVIET DESIGN

There is no question; design did exist in the Soviet Union! You can find evidence of this in your homes and at your dachas. These are things that we remember from childhood and continue using today. Some of them have become cult objects, symbols of the recent Soviet epoch.

In this section we present pilot projects and finished designs from all spheres of life: fashion and interior decorating, domestic life, games, hobbies and leisure, space technologies, mass industrial production and machine building.

We will uncover the names of Soviet designers that constructed the everyday Soviet life and tell the stories of ordinary things and unique design projects.

It is time to look at the pieces of soviet industrial and graphic design, arts and crafts and fashion from a new perspective. We need to see the artifacts oft the Soviet past as not just sentimental memorabilia but products of a systematic, functional, aesthetic and humanitarian approach to design.

THE MAIN STAGES OF DESIGN DEVELOPMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION:

1950s: The most important task in post-war USSR was to modernize industrial production. Designers had to think of fast and cost-efficient ways to produce consumer goods, whilst taking into consideration available production capacity, rather than people's needs.

1960s: Design became part of state policy. A network of art and construction bureaus is created, united by VNIITE. Design research is actively developed.

The Soviet government introduces Znak Kachestva, or Quality Mark, state quality standards on all goods. Consumer products become available to the general public.

1970s: The Soviet Union begins exporting more consumer goods; Zenit cameras, Slava, Polyot and Raketa watches, ZiL refrigerators and Moskvich cars become world famous. On the other hand, many innovative design projects did not come to fruition, even though production processes were more stable.

1980s: Soviet designers move from creating simple objects to developing complex systems (the Methodology of Design Programs). One example is a unique project of branding the 1980 Summer Olympics – a system of integrated urban design solutions and visual communications created by Soviet designers. In 1987 the first Union of Designers is set up in the USSR.

The Soviet Design system deteriorated in the 1990’s following the fall of the Soviet Union.

WAS INTERIOR DESIGN A MASS PHENOMENON IN THE SOVIET UNION?

Author - Nikolai Vasiliev

In the years after World War II, the ultimate dream of a Soviet office or factory worker was an apartment in a multi-story apartment building in the center of some city. Furniture was extremely scarce on the open market at that time, it was easier to buy something at an antique shop or even find something at a dump. Government flats, even in Moscow’s famous ‘House on the Embankment’, had state-owned furniture that was to remain there after the tenant left. Household appliances were also not readily available, so the prestigious high-rise apartment building on Vosstaniya Square in St. Petersburg boasted built-in kitchen equipment. By the end of the 1950’s, however, millions of people moved into new apartments that were too small for bulky furniture from earlier days. This phenomenon increased demand for new furniture and consumer appliances and the consumer started to become discerning. The heavy-handed Art Deco of old radios gave way to an elegant modernism, which was not quite as minimalistic as in architecture.

While brown-style minimalism was something our designers would arrive at in the 1970’s, they were still at the turn of the 1960’s engaged in a lively search for ‘new aesthetics’. The Institute of Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE) conducted the search (‘new aesthetics’ being a euphemism as the term ‘design’ was ‘bourgeois’ in Soviet lexicology until the end of the 1970’s and never found use in relation to the Soviet Union). Large household appliances, such as refrigerators, almost immediately took up all the space in the small-sized kitchen: the second model of the ZiL fridges were already of a 60 cm standard width. Fashioning the door, handles and emblem of the fridge was a task for the designers. One might think that a systemic approach would stimulate the development of design, though in reality it was more of an impediment. The sought-after type-design practice limited creativity as long as a technocratic modernist maxim dominated the agenda. The goal was to develop the unique ideal shape for a function; after that occurred, the designer and architect would then have no role.

Small devices, especially pocket radios and electric shavers, gave designers more freedom. They not only designed them in rectangular shapes, but used more elegant trapeziums that were outlines similar to the small architectural forms of Khrushchev-era Modernism, such as kiosks and bus stops with V-shaped roofing. The evolution of preferred forms first started in the late 1950’s with trapeziums, moving on to shapes with rounded corners by the second half of the 1960’s. Rectangular boxes with sharp edges in the mid 1970’s completed the evolution of preferred forms.

Cabinet furniture also rapidly lost height as ceiling heights decreased, as did architectural space. The same trends were visible in fashion; skirts and hairstyles shortened at the same time, though for their own reasons. Wood particle boards replaced solid natural wood, wood carvings and metal plates gave way to smooth lacquered doors, and simple geometric outlines that were reminiscent of abstract forms from the 1920’s, replaced floral patterns. Chair and armchair designs became radically lighter, though wood still prevailed. Public interiors saw the introduction of metal and plastic, with the structural frame of metal posts becoming visible. Seats took on reverse cone or trapezium shapes.

There is a growing tendency for the buildings’ outer walls to be covered with murals (a major difference with western Modernism) and windows became glass walls. The Pioneers Palace, created by architects V. Yegerev, V. Kubasov, F. Novikov, I. Pokrovsky and M. Khazhakian in 1959-63, situated in Moscow’s Lenin Hills, today called Sparrow Hills, was one example of the then-new approach, with a team of young architects and painters creating a giant mural on its side.

It is characteristic that there are few complex presentations of those years’ architectural environments as well as publications of coherent interiors. It was extremely difficult to create such interiors, and one had to be a true enthusiast. The trade journal Arkhitektura SSSR (Architecture of the USSR) covered large-scale forms and occasionally public areas. Dekorativnoye Iskusstvo (Decorative Art) focused on mural painting as well as applied art, and Tekhnicheskaya Estetika (Technical Aesthetics) looked at aspects of ergonomics, rather than at style.

One of the key achievements was collaboration between architects and designers when designing built-in furniture for small-size flats. The designer Yuri Sluchevskydeveloped a system of modular cabinet furniture. Presented at the first furniture fair in 1956, it clearly stood out against other Soviet-produced items. Sluchevsky also developed at the end of that decade furniture for the famous Khrushchovka apartment buildings that sprang up around the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev.

To “catch up with the West,” the All-Union Furniture Design and Technology Institute (VPKTIM) was established in 1962.

There are only a couple of movies that showcase interiors such as ‘The Last Con-Artist’ (Vadim Mass and Yan Ebner, 1966) or ‘To Love a Man’ (Sergei Gerasimov, 1972). A coherent concept of object design, furniture and interior can only be traced retrospectively, mostly as a description of the leading position of mural painting and applied art in the USSR.

In journal publications, furniture models stay in the tideway of Eastern- and North-European designers that set the pattern for Poland, Czechoslovakia and some other countries. The furniture and tableware exported from these countries to the Soviet Union were extremely popular.

Whereas Scandinavian design was primarily geared to mass production, high profitability and the strong school of community architecture, the Soviet interior design – besides exhibitions – suffered from the absence of living environment designer (unless you count as such the designers of separate pieces of built-in furniture, integrated into small-size apartments and kitchens).

In practice, the synthesis of art and design manifested itself to a certain degree by saturating public spaces with works of monumental and decorative art. Private interiors were left to the discretion of owners, who would furnish them based on their tastes, budget and organizational talent.

FURNITURE

In the Soviet Union furniture design and large-scale manufacturing began to develop only starting from the end of the 1950s. The Communist party of the Soviet Union ordered a ‘fight’ against all architectural extravagances, which led to the adoption of standardized design and assembly techniques. The pre-war furniture was too large for the small Khrushchevka apartments. New light, compact furniture with simpler designs had to be created to match the new living spaces.

In 1962 this problem was solved with the creation of the All-Union Institute of Furniture Design (VPKTIM). It was a centralized government institute that determined standards for furniture design and production.

A specialized method of interior design was needed for the new, small format apartments. The main development in furniture design of the period was the creation of modular furniture. Experimentation in this area of Soviet design is synonymous with the name of Yuri Sluchevsky, one of the most influential Soviet furniture designers. Besides mass produced pieces, custom furniture design and assembly also existed. However, such luxuries were available mostly to members of the nomenclature and the Soviet elite.

HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES

In the 1950s, to catch up with modern technological innovations, many Soviet household appliances were either directly copied from Western models, or created using Western models as prototypes. However, by the end of 1960s, independent Soviet designs came to the forefront.

Household appliances of the 1960s, like the small interiors of Soviet apartments that they were designed for, had a unique character. This is evident from their proportions, factory logos, materials used and even their names, such as ZiS-Moskva refrigerator, Riga-60 washing machine, Chaika, Raketa and Saturn vacuum cleaners, etc. The design of such objects had gone a long way from the aero-cosmic style of the 1930-50s to the original geometric modernism of the 1960-70s featuring models that were significantly different from European designs.

The ZiS-Moskva refrigerator has become a symbol of an eternal appliance. In the 1970s, the ZiL factory developed new, promising refrigerator models, commissioning both Soviet designers from VNIITE and Raymond Loewy’s famous American design studio. However, even though a number of limited editions and prototypes received various awards, none of them were put into mass production.

SPACE

The launch of the Sputnik, first artificial satellite into orbit (1957), the launch of the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space (1961) and other Soviet achievements in space exploration, had significant influence on style solutions in graphic and industrial design. In the late 1950s – early 1960s fluid lines and shiny metallic surfaces become common in household objects. Some examples of this trend are the 'cosmic' designs of Raketa (‘Rocket’), Chaika (‘Seagull’) and Saturn vacuum cleaners.

The same factories that worked for the military and space industries also produced consumer goods, making use of military technological innovations. As a consequence, objects manufactured by these factories were of high quality and very durable. For example, the first photograph of the other side of the moon was taken in 1959 with Yenisei photographic equipment, manufactured at the Krasnogorsk Mechanics Factory. Over the years, factory workers received many letters from astronauts via official post thanking them for the high quality of their photographic equipment, saying that it never failed, even under the most difficult conditions.

Another example is the Petrodvorets Watch Factory that produced watches with the unique Raketa (‘Rocket’) mechanism for everyday use as well as special models for pilots, divers, members of polar expeditions and astronauts.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EQUIPMENT

After World War II photography became the national Soviet pastime. The first post-war factories used captured production lines and designs that were shipped out of Germany. However, after the success of Soviet photographic equipment at Expo ‘58 in Brussels original Soviet designs were put into mass production. These designs rapidly won over the domestic market and became one of the key export goods for the Soviet Union. Leading Soviet factories KMZ and Lomo, like their Japanese counterparts, focused on producing affordable models, which became, unlike the professional cameras, a field for design innovation.

Lubitel-166 (‘Ammateur-166’) was both the most stylish two-lens camera and the most mass produced model. Smena-8m, in its turn, introduced millions of Soviet children to the magic of photography. Lomo-compact became the first camera to start a movement in photography – ‘Lomography’. From the 1960s onwards the Krasnogorsk factory manufactured modernistic style models that are recognizable all around the world. The Zenith-E model became the epitome of this geometric and functional design.

АВТОДИЗАЙН

Despite the success of the Pobeda (‘Victory’) car, designed by V. Samoilov and A. Lipgart in the 1940s, the Soviet automotive industry was based almost entirely on Western designs. Not all brands and types of cars (which in the Soviet Union meant not all factories and design departments respectively) were known for innovation. The most cutting-edge designs were those of off-road vehicles, since these were military-oriented, like the famous Niva car, as well as mid-size cars.

Unlike the design of Volga and Lada cars that evolved similar and parallel to certain Western brands, automotive engineers of the Moskvich cars looked towards national designs. Starting from the 1960s most Soviet car designers moved away from imitating western trends and began to work with original designs. This was a period of artistic freedom and search for new ideas for many Soviet designers. The most renowned designer was Yuri Dolmatovsky. Unfortunately none of his designs, including the famous VNIITE taxi, were put into production. By the 1980s the majority of automotive factories reverted to borrowing Western designs.

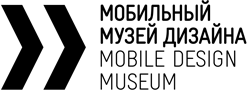

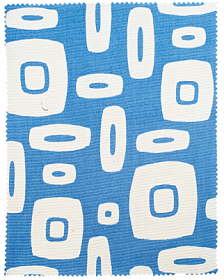

FASHION

Following the International Youth and Students Festival in 1957 and the Christian Dior show in 1959 international fashion trends started to spread to the Soviet Union. The main developments in Soviet fashion design were created at the All-Union Fashion House (ODMO). However, collections that were created by the ODMO designers were meant only for Western fashion shows. As a result the names of such Soviet fashion designers as Vyacheslav Zaitsev, Lina Telegina, Tatyana Osmerkina became known to the international fashion industry.

At the same time fashion design for the average Soviet consumer was falling behind European trends. All of the more interesting pieces of clothing were made on an individual basis at small dress-studios or by local tailors, whose names, for the most part, remain unknown. Under conditions where ready-to-wear textile goods were in short supply almost all Soviet women knew how to knit and sow at least at a basic level. Leaflets with dress and knitting patterns from Soviet and foreign fashion magazines as well as from such popular publications as Rabotnitsa and Krestianka were collected in every Soviet household. The unique designs that were hand-made by our mothers and grandmothers still look fashionable today.

PORTABLE DEVICES

Although international travel was a rarity for Soviet citizens, domestic tourism was growing in popularity. This caused airplane and train ticket prices to go down, tourist guides became widely available and discount vacation packages were distributed by trade unions. More importantly, this influx in tourism resulted in a demand for a variety of portable devices. One of the most unusual examples of these products was the Tourist-1 guitar, limited edition, 1970s. These guitars had built-in amplifiers and loudspeakers and were designed to be used outdoors, when camping or during picnics.

Some of the other interesting products that were designed for Soviet leisure are the extremely small Era radio, the micro-format and half-format Narciss (‘Narcissus’) and Chaika (‘Seagull’) cameras, magnetic chess sets and, of course, collapsible plastic cups. A portable glass-size water heater was also an essential tool in a Soviet household. It was used both on the road and, for example, in student dormitories.

Other Soviet consumers were interested in devices that would help them look presentable during, for example, business trips. To meet this need such ordinary yet imaginative devices as the mechanical Sputnik-3 razor, a small portable iron and a travel folding hanger-with-brush were designed. For fans of outdoor activities such products as the Yermak backpack, boat motors and kayaks were produced.

|

|